The Arciform team has been hard at work restoring the historic Fried-Durkheimer House, also known locally as the first Morris Marks House, and the extensive renovations are nearing completion. Recently, we were able to take a look at the progress and talk to project manager Joe McAlester and the Arciform crew about this impressive Italianate structure.

It was a beautiful sunny day, the sky azure blue and punctuated by fluffy clouds. The house stood encircled by a chain-link fence, its fresh coats of pale blue and white paint gleaming in the sun. Joe graciously invited us inside, gave us a tour, and introduced us to the crew who were hard at work painting and finishing various elements. As construction is one of the fields that is considered essential, the Arciform crew has been able to continue their work during the pandemic by wearing masks and keeping a safe distance from others.

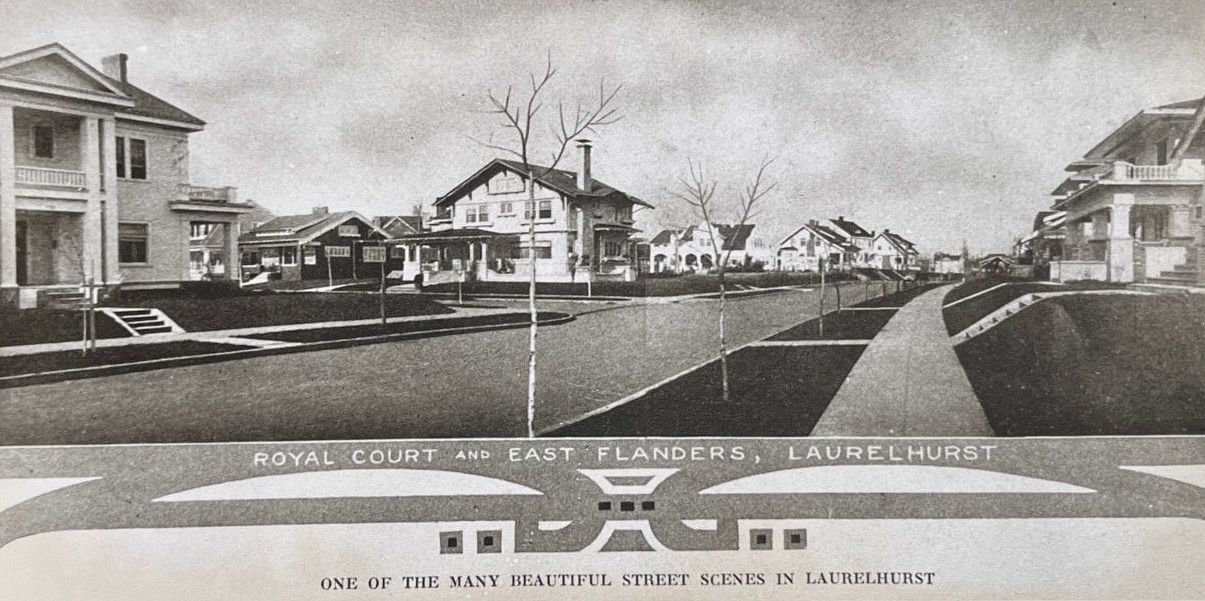

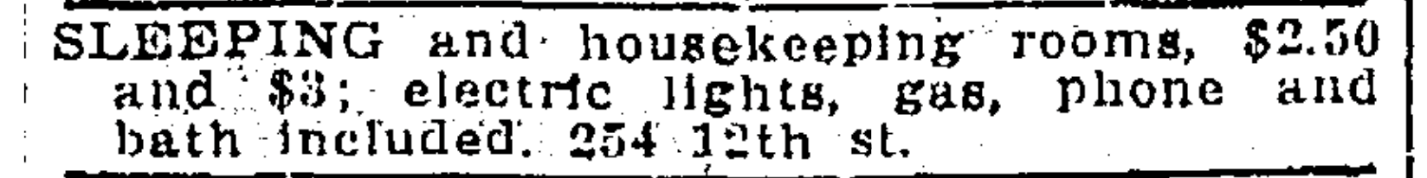

This probably isn’t the first time that masks were worn in this house to ward off a virus. Just a century ago, a novel influenza virus infected one-third of the world’s population, possibly including inhabitants of this home. Though it was originally built in 1880 as a private residence for the Morris Marks family, by the turn of the century the building was functioning as an 11-room boarding house. In the early 1900s, the house was advertised in the Oregonian as having, “light, airy, heated rooms, [and the] finest home cooking,” and a 1917 Oregonian ad, just a year before the 1918 pandemic hit Portland, promised residents “electric lights, gas, phone, and bath” for $3 a week.

Arciform crew members Benjamin Houser (left) and Roger Muller (right). Photo by Gingi Tilbury.

Talking to the crew, it was clear that the value of this home as a historical, cultural, and architectural record is in the forefront of their minds. Standing in a sun-filled room on the first floor, beneath an ornate 19th century chandelier, Arciform site lead Roger Muller and carpenter Ben Houser chatted with me about this house’s importance and the sometimes challenging process of working on it.

The original ornate banister. Photo by Gingi Tilbury.

“This is one of the last of its kind. You don’t have too many Italianates left in the downtown core,” Roger said. “It’s a good symbol, especially right now. This house is 140 years old and is still here,” Ben added. Agreeing, Roger continued, “It’s survived a lot of big events in our history – world wars, the 1918 influenza pandemic, the Great Depression – and hopefully it will continue for another 100 years. This house is already 140 years old. But when the trees were harvested, they were probably at least 200 years old, so that makes the wood in this house at least 340 years old. It’s remarkable.”

The pride these craftsmen take in their work is evident. “Did you get a shot of these doors yet? This is one of my favorite things,” Ben said with infectious enthusiasm, sliding the pocket doors out from their recessed hollow. Painter Rene Flannigan had explained to us earlier that they actually boiled the paint off the original door hardware, which now shines in the newly painted doors.

The original door hardware was salvaged by Arciform. Photo by Gingi Tilbury.

“Did you get a lot of pictures of the moldings and all the details?” Roger asked, showing us the original and reproduction wainscoting – the new pieces perfectly indistinguishable from the old.

This Italianate beauty has an abundance of intricate millwork; the Arciform crew repaired what they could and reproduced sections they couldn’t. Site lead Jack Ouska explained via email that “The vast majority of the restored and replicated pieces on this project were done by Arciform carpenters in the field – using basic hand tools, some power tools, and their carpentry skills.”

As we talked about why it’s important to save old houses like this one, Roger said, “We have enough cookie-cutter homes out there. This house is so unique. You could replicate something like this, but who’s going to? For starters, the moldings are so intricate. And the cost it would take to replicate these details is cost prohibitive.” Both Roger and Ben agreed that new houses just aren’t made with the same attention to detail and craftsmanship.

“When doing renovation, so many people don’t take the time to research what is proper for the style and time period of their home. They take out these great old double-hung windows and put in vinyl windows. We don’t do that. This attention to detail is what Arciform is known for. We can restore and modernize aspects of a structure, but without sacrificing any of the architectural integrity. That’s so important,” Roger said.

Door repair by Arciform

With so much intricate woodwork to be repaired or replicated, Arciform played an important role in the restoration of the Fried-Durkheimer House. Their skilled craftspeople recreated an elaborate window that was damaged beyond repair; replicated the front doors, salvaging decorative parts from the originals; repaired, replaced, and re-glazed numerous original window sash; repaired and replaced numerous interior doors; and produced millwork for various repairs.

Reproduction of one of the building’s ornate windows. Photo by Arciform.

Other details receiving careful attention include the restoration of the marble fireplace, which has become a special project for site lead Jack Ouska. “Jack is extremely enthusiastic about the fireplace, so everyone wants him to be the one to finish it,” said Ben. “For the repair,” Joe explained, “we are going to reset the pieces in mortar and then grout all the cracks. We won’t be trying to make it look seamless; the cracks will still be visible, giving it some character.”

The original marble fireplace will be repaired by site lead Jack Ouska. Photos by Benjamin Houser (left) and Gingi Tilbury (right).

Arciform founder and co-owner Richard De Wolf sourced the salvaged antique light fixtures on the first floor, some of which were donated by the Architectural Heritage Center. The dramatic gilt bronze chandelier was once a gaslight fixture, a common method of lighting during the mid-1800s before electricity became the norm. (You can read about the history of gaslight fixtures and see fixtures similar to the one used in the Fried-Durkheimer House in the National Park Service’s article titled “Gaslighting in America: A Guide for Historic Preservation.”)

The process of restoring the house wasn’t always easy for the crew. “If you’d seen this place when we first started, it’s a pretty phenomenal transformation,” Roger said.

Joe said, “It was pretty bad.” The house had been empty since the 1990s and was occupied by squatters for years.

“It’s been kind of a love-hate relationship. I think we’re now all starting to love it more, but there were times when we would come here before the roof had been repaired . . . We had blue tarps on the roof,” Roger said, gesturing upwards towards the ceiling, “and we would come here in the middle of the winter, and it’d be raining, there were five gallon buckets everywhere throughout the house, and the water would just pour down on your tools.”

Laughing, Benjamin added, “It would be ten degrees colder inside than it was outside; to warm up, you’d have to go outside!”

“It was just miserable,” Roger continued. “I think we’re now all starting to love it more, but there were times when we would come here before the roof had been repaired . . . it’d be raining, there were five gallon buckets everywhere, the water would just pour down on your tools. It was kind of a depressing job site for a long time. Half the windows were missing. We had plywood up. It was kind of a depressing job site for a long time. Now that it’s this far along, we enjoy working here again. But there was a time when, you know, we thought ‘Are we ever going to see the end of this?’ We do this on a regular basis, but . . . ” Roger paused, “this one was a little harder.” Roger and Ben said the last sentence together, in almost perfect unison.

“Even though we work on things like this all the time, when we first started working on this house, a lot of us felt like, ‘This thing is so far gone.’ But now, with the proverbial light at the end of the tunnel, it’s just remarkable how far we’ve come,” Roger said.

As our conversation concluded, Roger again emphasized why saving these historic structures is worth it, even when it’s challenging: “If you start eliminating one house or one building here and there, the next thing you know you’re losing the fabric and the identity of the city.”

Jack Ouska, the primary site lead for this project, wasn’t on site the day we visited, but he shared his thoughts with me via email about the exciting journey this house has taken, both literally and figuratively:

Jack Ouska, site lead for the Fried-Durkheimer restoration. Photo by Christopher Dibble.

“Nothing was on paper as to how you shore up a three-story home that is 138 years old, balloon framed, with no subsiding or subfloor, cut it in half vertically, like slicing a tall wedding cake from top to bottom, and have it survive, intact, for a mile and a half ride through Portland. I remember Richard [De Wolf] looking at me on our first site visit and asking, ‘What are the chances of this home making it to its new location without collapsing during the move?’ I told him, ‘No problem.’

Jack goes on to say, “Richard, Joe McAlester, and I came up with a plan, and as you can see, it worked. Credit also goes to Sam Gray, one of our site leads who took the reins while I went on vacation, finishing all the shear walls and brace panels. He was also our ‘cake slicer.’ Sam did a remarkable job, as did many others who lent their skills.”

Karen Karlsson, Rick Michaelson, and Richard De Wolf, the current owners of the Fried-Durkheimer House, certainly share similar sentiments about how important buildings like these are in preserving Portland’s history and culture. They headed the efforts to save this house in 2016, purchasing the house for $1, cutting it in half, and moving it to its new location at SW Broadway and 6th, which took an incredible amount of time, money, and effort.

Richard De Wolf explained that the guidance of experienced architects is essential, “especially when converting a building from residential to commercial,” as is the goal with this project. For the restoration of the Fried-Durkheimer House, Arciform consulted Paul Falsetto, an architect with specific expertise in historic preservation. Paul has developed preservation and rehabilitation plans for many buildings listed on the National Register of Historic Places. Richard says, “Paul was great to work with. His extensive experience with commercial architecture, along with his passion for historic buildings, helped make this project a resounding success.”

Preserving historic buildings is important and not only because people love them. Places hold memories that connect us to our history, culture, and community in essential ways, both individually and collectively. Architect Paul Falsetto explains:

“The history of a place is encoded, in part, in its properties and structures. They provide evidence of the values and lifestyles of generations past, made real and tangible for us to experience today.”

--Paul Falsetto, architect

“You can see and touch the historic building façades built by craftsmen of that time. You can stand inside the building spaces and experience light and volume much like previous inhabitants did. These properties act as a through line of narrative from past to present that helps bind a community together in a meaningful manner. Conversely, if you lose a property of historic significance, such as what very nearly happened with the Fried-Durkheimer House, you lose forever a piece of the story of what makes a place real and unique.”

This is what makes the work done by Arciform so important: it preserves our community, deeply connecting us to place and history.

Joe McAlester and Roger Muller work on final details. Light fixture donated by the Architectural Heritage Center. Door restored by Arciform. Photo by Gingi Tilbury.

The day after our interview, project manager Joe McAlester sent me a lengthy list of all those currently involved on this project. Joe wanted to be sure to give credit to the entire Arciform crew responsible for restoring this important cultural landmark: Jack Ouska, Sam Gray, Roger Muller, Darin Puntillo, Benjamin Houser, Quenten King, Christopher Burgos, Taylor Rademacher, Brian Hoffman, Jacob Hawkins, Peter Chakmakian, Don Golden, Noah Schultz, Rene Flanigan, Travis Sergi, Derek Eshenaur, Brad Horne, Stephyn Meiner and Isiah Dorn.

Reading through this list of names, it’s reminiscent of an award-winner’s Oscar night thank-yous, and that seems somehow appropriate for such an impressive accomplishment.

See More Stories